Where the Mumbai Hyderabad highway passes into the Osmanabad district of Maharashtra state, a medieval structure comes into view, its long fortification walls with its many bastions a testimonial to India’s ancient glory.

Naldurg Fort was built sometime between the 10th and 12th centuries by Raja Nalraja, a vassal of the Chalukya kings of Kalyani. The structure changed hands over the following centuries as new empires captured the Deccan Plateau, starting with the Bahamanis, then the Adil Shahis of Bijapur, the Mughals in 1686 AD, and finally the British.

The environment around this ancient fort is barren, the land too arid to support anything more than thorny scrubs, but the Bori River, on whose banks Naldurg Fort is built, would have ensured a steady supply of water to the fort’s inhabitants in times past.

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

The interior of the fort is built around a large compound, which is surrounded by several small buildings, including a masjid.

Scheme for Protection of Monuments

Ancient monuments in the state of Maharashtra are owned and protected by the Directorate of Archaeology & Museums, referred to as the Archaeology Department.

In 2007, the state’s Archaeology Department introduced a scheme to conserve ancient monuments. The conservation scheme was called Maharashtra Vaibhav State Protected Monuments Conservation Scheme. It was formulated under the provisions of the Maharashtra Ancient Monuments, Archeological Sites and Remains Act of 1960, Section 15.

The state’s conservation scheme allowed societies and corporates to take over guardianship of protected monuments, to “adopt” them, as it were, for a stipulated number of years. The guardian would be responsible for the maintenance and conservation of the structures and would bear any expenses incurred in performing those responsibilities. The idea was to attract corporates that had a keen sense of social responsibility.

In 2011, the state approved a bid by a Solapur-based construction company called Unity Multicons Private Limited to adopt Naldurg Fort for a period of ten years. The agreement with the company was signed on August 26, 2014, with the state being represented by the director of the Directorate of Archaeology & Museums.

Four years later, on a visit to Naldurg Fort, BEAG members were shocked to find several irregularities in the maintenance of the historic monument.

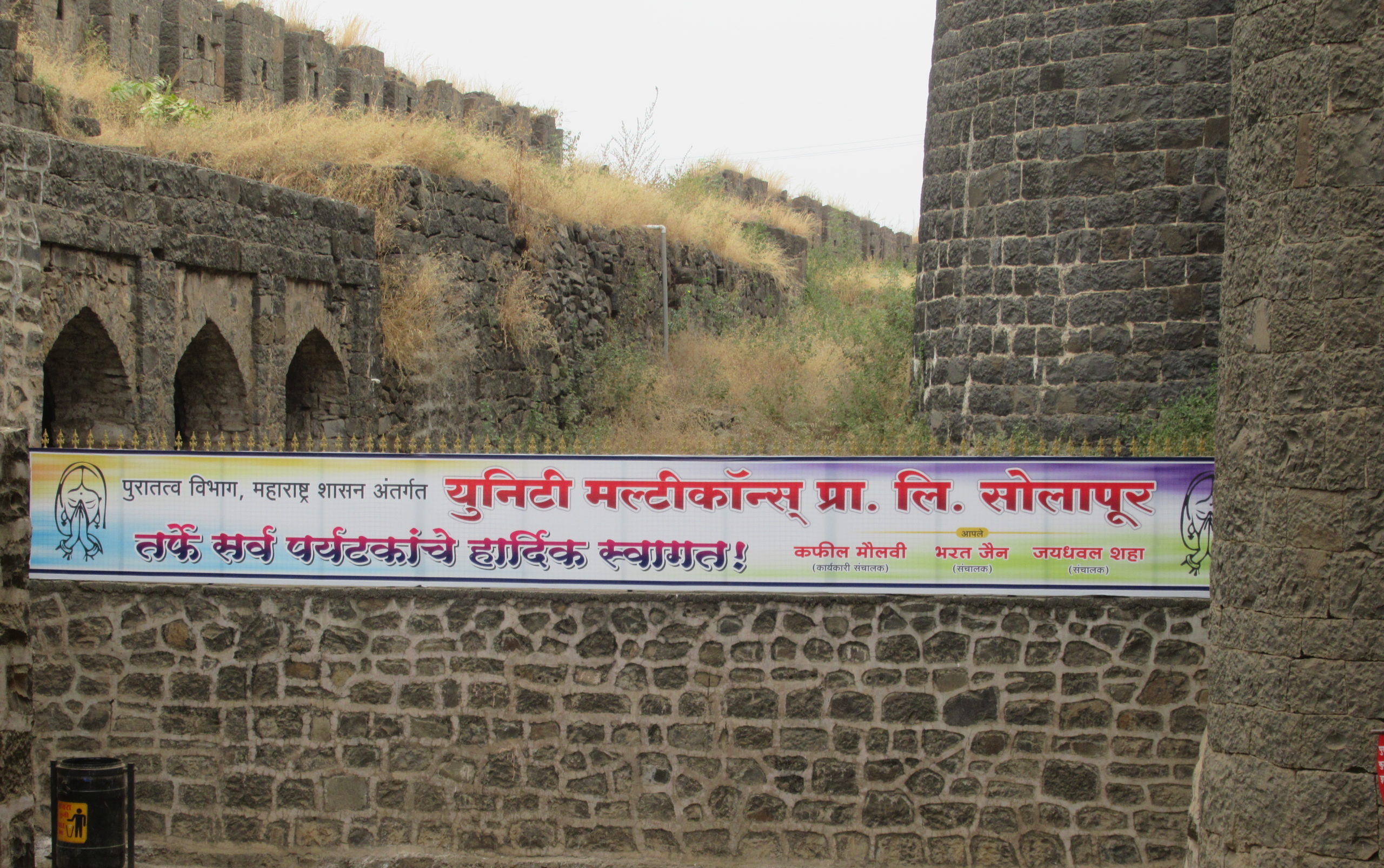

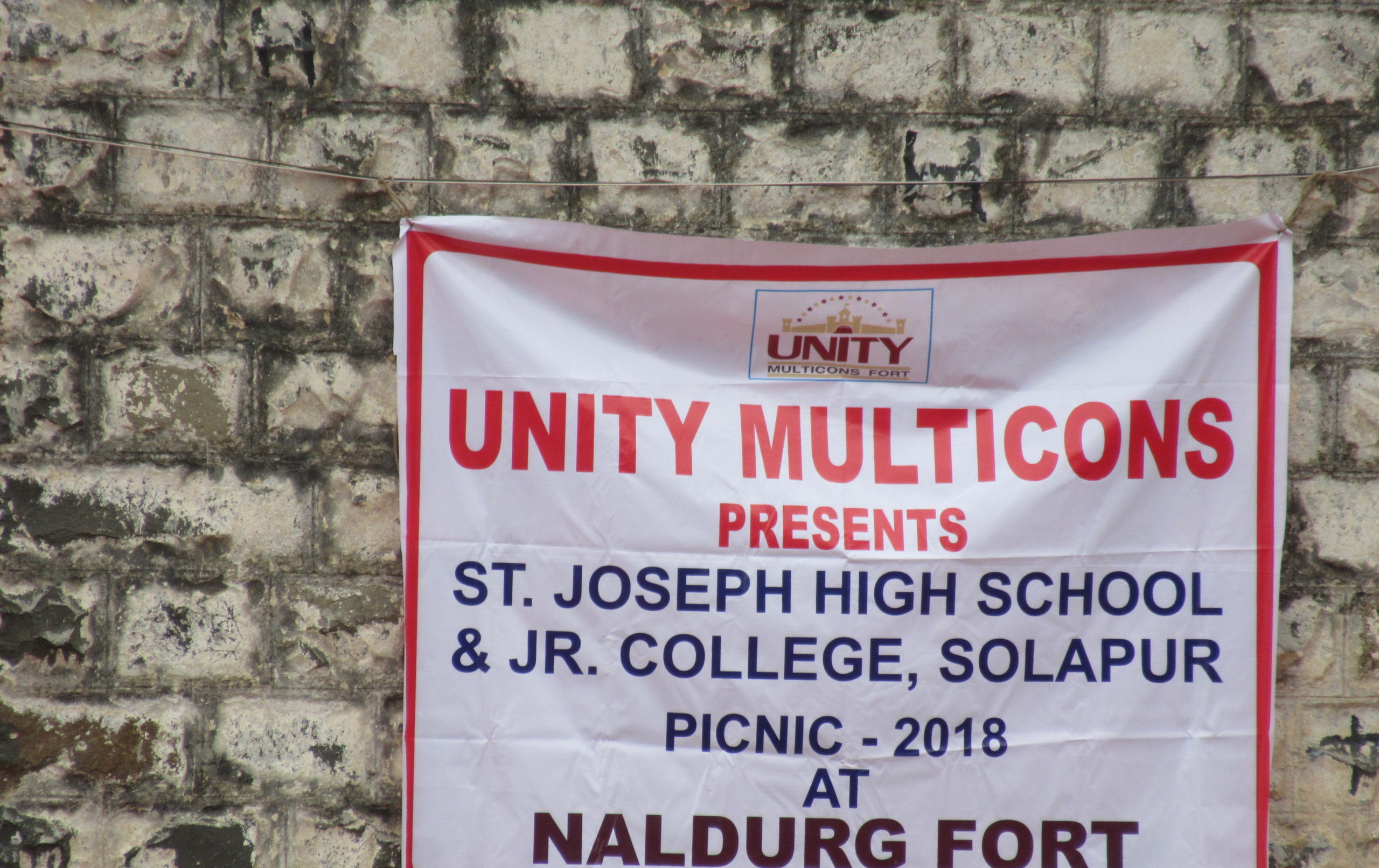

Huge signs boards had been placed outside and inside Naldurg Fort with little regard for their appropriateness or their placement.

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

The sign boards carried no mention—not even a logo—of the state Archaeology Department, which is the rightful owner and custodian of the fort.

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

Private vehicles and excavator machines were parked throughout the interior of the fort. It was evident that existing structures were being gunited and painted and totally new structures were under construction.

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

Artifacts and inappropriate installations such as elephant sculptures and Urli bowls had been placed throughout the fort.

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

Stalls that looked like large wood crates had been placed in every section of the fort in an attempt to create a bazaar-like environment.

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

No tour guides were available, nor were there any boards providing historical facts about the fort. It was apparent that the company that had been appointed the guardian of this ancient monument was not focusing on its historical importance but was promoting it as a venue for amusement activities such as boating, horse riding, archery, rifle shooting, sword fights, overnight picnics and even destination weddings.

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

Outside the fort, more irregularities were plainly in evidence. Water was being drawn from the Bori River for various uses and new bunds were being constructed on the river on which crops were being planted.

Vegetation was being cleared in the areas surrounding the fort and being burned on site.

Picture Credits: BEAG Archive

It was apparent that none of the work being carried out inside or outside the ancient monument adhered to any standard conservation norms.

BEAG members met the director of the Directorate of Archaeology & Museums to apprise him of their findings and were shocked to discover that the changes at the fort was being carried out without permission from the state.

The agreement signed with the company had explicitly prohibited the construction of any structures and had clearly stated that that the guardian company must seek permission from the state before undertaking any construction—be it a toilet or a parking area—or staging any events such as light shows and exhibitions.

BEAG pointed out that the state should have monitored the conservation of the monument and made sure that the guardian company would follow the basic

standard procedures and rules for preservation, restoration and conservation of ancient structures.

BEAG urged the Archaeology Department to put a stop to all the work being done at the fort, revoke the agreement with Unity Multicons, and ensure that the company be made to bear the cost of the restoration work that would now have to be undertaken to bring the monument to its original condition.

The “conservation” of Naldurg Fort had set a bad precedent for all present and future adoptions of monuments under the Vaibhav scheme.

The director of the state Archaeology Department promised to look into the matter and keep BEAG informed of the action taken by his department.

Based on BEAG’s representation, the construction work was immediately stopped by the state Archaeology Departmentandappointed an architect to assess the damage and present a report for restoration.

Unfortunately, the architect that the department appointed was not a heritage conservation architect and the report that he submitted in March 2019 did not meet basic norms.The report was titled ‘Naldurg Fort, Osmanabad, Restoration Proposal’.

Not only was the report unsigned, it did not even specify the terms of reference, which are supposed to include the objectives, scope and methodology of the evaluation.

Strangely, the report accepted all the irregular existing structures and in fact suggested that various improvements be undertaken. It also proposed, against all norms of conservation and preservation, sports such as archery, fort rappelling, and horse riding.

After studying the report, BEAG urged the state Archaeology Department to not accept the report and to instead have the entire development proposal reviewed by an architect with expertise in heritage conservation. BEAG also reiterated its request to the Department to immediately revoke the agreement with Unity Multicons and to recover all restoration costs from the company.

BEAG was relieved when the state Archaeology Department directed the Assistant Director, Aurangabad, in November 2019, to appoint architects to prepare a new site management plan for Naldurg Fort.

Since then, the state Archaeology Department has not initiated any action, ostensibly due to the Covid pandemic.

But BEAG continues relentlessly to press the department to appoint a heritage architect and to also ensure that steps be taken to correct the irregularities that occurred during the adoption of Naldurg Fort.

BEAG has been given to understand that the adoption scheme itself is under review.